In the wake of the war in Gaza, we have seen a large number of young people talking about reading the Qur’an for the first time, and in some cases actually converting to Islam as a result. I’m not sure how widespread or genuine this phenomenon really is — after all, TikTok is more a caricature of society than a reflection of it — but all things being equal, it is surely beneficial for people to read other people’s sacred literature with an open mind (rather than just skimming it for quotes to use as ammunition). That said, the Qur’an is not an easy read, and it is easy to misinterpret. I first read extracts from it when I was ten years old and looking for a religion; it struck me as terribly dry, and I moved on quickly to Buddhism. Years later, I was moved to read it again after conversations with Muslim friends and still wasn’t terribly impressed. The Qur’an doesn’t immediately make you say “Wow, this is deep” in the way that the Dao De Jing or the Upanishads do; neither does it present a logical-sounding argument in the way that Greek or Buddhist philosophy does. It just seemed like a duller version of the Old Testament, which was largely because translators had gone to some trouble to make it sound just like that. It wasn’t until I had read a fair amount of Sufi literature and had some long conversations on the subject that I really started to appreciate the Qur’an, and it’s only quite recently that I’ve started reading it in Arabic, which is when you really start to appreciate it.

It should be clear by now that I am far from being an authority on Islam, but I would still like to share some basic information and tips that might be useful for people approaching the Qur’an for the first time. The first is simple: take everything you think you know about Islam and Muslims and put it on one side. Misrepresentations aside, Muslims are an incredibly diverse community, and there is as much variation in Islam as there is in Christianity. Much of what we assume to be integral to Islam actually isn’t in the Qur’an at all or is only alluded to vaguely or ambiguously. Half the secret to reading the Qur’an is simply a matter of reading it without preconceptions; the other half is what I will try to clarify here. Unlike my usual opinionated blog posts, I will for the most part try to stick to accepted facts (including facts about opinions, as in “These people believe this”). When I do insert my opinion, I’ll try to make it clear that it is just that.

What is a Qur’an?

Just as “bible” literally means “book”, “qur’an” means “reading” or “recitation”, and more specifically, “revelation”. Consequently, before we can say what the Qur’an is, we need to ask what a qur’an is. It is widely accepted among Muslim scholars that the whole universe is in a sense a qur’an (which reminds me of Spinoza’s comments on this subject) and many thus embrace science as way of “reading” this revelation. More controversially, Sufi mystics sometimes hold that each individual, being a manifestation of God, is also a qur’an, hence the injunction to “read your own Qur’an” meaning “Know thyself.” But here we are concerned with scriptural revelations, and the book that we call the Qur’an is the latest to be revealed by God to a series of prophets starting with Adam and ending with Muhammed. In fact, a prophet in Islam is defined as someone who has received a revelation from God for the benefit of humankind; Abraham, Moses and Jesus are counted here as prophets, and some Muslims, quoting the Qur’an’s reference to sending a prophet to every nation, allow that some founders of other religions, such as Zoroaster or the Buddha, might also be prophets. Be that as it may, Muslims universally accept the Tawrat (Torah), Zabur (Psalms) and Injil (Gospel) as revelations, though they also consider the texts to have been corrupted. It follows that all true religion, regardless of what name it goes under, is seen as being Islam in the sense of peace or submitting to God (the root SLM gives both “salaam”, meaning “peace” and “islam”, meaning “submission”). Likewise, all those who attempt to submit themselves to God are seen as being, in some sense, Muslims, and the term is used in this sense in the Qur’an, rather than as a way to distinguish the followers of Muhammed from those of, say, Moses or Jesus. Thus terms like “unbelievers” in the Qur’an do not refer to followers of other religions, but rather to those Arabs who specifically opposed Islam.

Some Historical Context

Given that Muslims see the Qur’an as a final revelation to complete these earlier revelations, it is not surprising that readers from a Judeo-Christian culture will find many characters and themes familiar, and react positively or negatively depending on their attitudes towards Christianity or Judaism (which were largely negative in my own case). To insert my own (non-authoritative) opinion here, I might say that the mythos of Islam — in the sense that I use in “Harry Potter and the Spitting Haredim” of an imaginal motivational framework for religious ethics and practices — is based on that of Judaism and Christianity. However, it’s worth noting that the Christianity we see in the Qur’an is closer to the Ebionite variety (which saw Jesus as a human Messiah) than the Pauline version that is familiar to us nowadays, and the Christians living in Mecca may even have been of this persuasion. Likewise, the so-called paganism of Muhammed’s time was somewhat different from what we understand by the term, and was really more of a mishmash of Abrahamic beliefs with local customs and deities. (Personally, I dislike the use of the word “pagan” in this context, but that’s another story.) Some of Islam’s critics make much of the fact that Allah was worshipped by the “pagan” Arabs and even sometimes equate him with the completely different Al-Lat (thought to be one of Allah’s daughters); however, Allah was believed by Arabs of all persuasions to be the god of Abraham. Islam was thus more of a radical reform movement within existing beliefs rather than a completely new religion.

But what, exactly, was Muhammed seeking to reform, and what role does the Qur’an play? Even before the revelation, Muhammed was both a religious and a political rebel. He was identified as a hanif, literally meaning “one who turns away” and was thus part of a growing movement of people who rejected traditional beliefs in favour of a kind of non-aligned monotheism. They rebelled not only against what they saw as superstition but against a social order described well by Karen Armstrong:

The old communal spirit had been torn apart by the market economy, which depended upon ruthless competition, greed, and individual enterprise. Families now vied with one another for wealth and prestige. The less successful clans felt that they were being pushed to the wall. Instead of sharing their wealth generously, people were hoarding their money and building private fortunes. They not only ignored the plight of the poorer members of the tribe, but exploited the rights of orphans and widows, absorbing their inheritance into their own estates. The prosperous were naturally delighted with their new security; they believed that their wealth had saved them from the destitution and misery of badawah [nomadism]. But those who had fallen behind in the stampede for financial success felt lost and disoriented. The principles of muruwah [the tribal code] seemed incompatible with market forces, and many felt thrust into a spiritual limbo. The old ideals had not been replaced by anything of equal value, and the ingrained communal ethos told them that this rampant individualism would damage the tribe, which could only survive if its members pooled all their resources.

Many verses in the Qur’an speak directly to this situation:

Have you seen one who denies the Day of Judgement?

Who turns away the orphan,

and who does not urge the feeding of the poor?

So woe to those who pray

but whose hearts are not in their prayer.

Those who do things only to be seen by others.

Who are uncharitable even over very small things.

(Surah al-Ma’un, trans. Maulana Wahiduddin Khan)

The Qur’an did not appear in one go but was revealed (or composed, if you are a non-believer) in episodes (surah) of varying length, often in response to questions or events; in this case, the surah is thought to refer to a specific person, possibly Abu Sufyan, the prophet’s father-in-law, who had just driven an orphan child away with a stick. The meaning here is clearly both specific and more general; Muhammed was talking about particular people in Mecca, but the surah clearly refers to a class of people (I’m hearing people mutter “Tories” here).

The specific-general distinction needs to be kept in mind in many places, particularly when reading some of the more controversial verses. Islamophobes are fond of quoting verses that refer to killing “unbelievers” while ignoring the fact that these were revealed in the middle of an actual war, and killing people is what you’re supposed to do in a war. Whatever more general or even esoteric meanings people may claim for such verses, they also clearly contain specific instructions about dealing with specific people, and we need to bear this in mind when drawing conclusions from them. Surah Al-Anfal, quoted by both Islamists and Islamophobes alike, is an obvious example given that anfal means “spoils of war” — a reference to verse 41: “Know that whatever spoils you take, one-fifth is for Allah and the Messenger, his close relatives, orphans, the poor, and travellers, if you believe in Allah and what We revealed to Our servant on that decisive day when the two armies met” (referring to the battle of Badr). Verse 39 of this surah is often quoted as something like “Fight them until there is no more unbelief, and all worship is of Allah alone.” But here is Khattab’s translation (which is fairly typical): “Fight against them until there is no more persecution, and ˹your˺ devotion will be entirely to Allah.” Note that here, the Arabic word fitnah is translated not as “unbelief” but as “persecution”, and I've also seen it translated as “oppression”, “aggression”, “sedition” or “tumult”. “Persecution” is the most common and makes the most sense here, given that the war started because Muslims were being persecuted in Mecca. It is thus not a call for a religious war on the whole non-Muslim world but an injunction to fight against a specific group of oppressors, and is both preceded and followed by injunctions to leave them alone if they desist. This ties in with “And fight in God’s cause against those who wage war against you, but do not commit aggression — for surely, God does not love aggressors” (2:191, trans. Maulana Wahiduddin Khan).

There are many examples like this to show that both historical and textual context are important and that any one verse may have a specific meaning, a general meaning, or both. But it gets even more complicated.

Interpreting the Qur’an

We have seen that the Qur’an is believed to be in some sense the word of God; in fact, people are fond of saying “Muslims believe the Qur’an to be the literal word of God.” However, this sentence is ambiguous; does it mean that the Qur’an is literally the word of God, or that in the Qur’an God is speaking literally? The former view is held by the majority of Muslims; the latter, by a vocal fringe. The idea that everything in the Qur’an should be taken as literally true was ridiculed way back in the Middle Ages, not least because a literal interpretation of some verses would not only be absurd but would contradict basic Islamic doctrine. For example, the Ayat al-Kursi or “throne verse”, which is recited daily by millions of Muslims, contains the line “His Throne includes the heavens and the earth” (Pickthall’s translation) or “His Seat encompasses the heavens and the earth” (Khattab), but it would be ridiculous if not blasphemous to assume that God is literally sitting on top of the world; why then, should we assume that depictions of Heaven and Hell in the Qur’an must be literal?

In fact — and here for once I can speak from a position of authority — it is nigh-on impossible to have a normal conversation without metaphor, let alone a spiritual one. When you say you have run out of milk, no running is involved; when you say you see what someone means, the meaning is not displayed in front of your eyes; if someone demolishes a theory, they are not using explosives or wrecking balls. We understand abstract thought in physical terms, and the more abstract the idea, the more metaphorical we need to be to get a grip on it, so to speak. Thus even when we talk about a “literal” interpretation of the Qur’an, it cannot be totally literal; the debates necessarily take place in the extensive middle ground between word-for-word literalism and poetic fancy.

There are also different ways to interpret “word of God”. The first, and simplest, is that the Qur’an was transmitted by God to Muhammed during his life in much the same way as I am writing this to you. In other words, it was created with specific words at a specific time and for a fairly specific audience. This is the view of the Mu’tazila school and was dominant up until some time in the ninth century, when it started to be replaced by what is now the standard Sunni view that as the word of God, the Qur’an must be coexistent with God (much like the Christian doctrine that Jesus is coexistent with God rather than coming into existence at the moment of his historical birth). Both views may be contrasted with that of the Ismailis, who hold that the original Qur’an (Umm al-Kitab or “mother of the book”) exists only as divine light (nur), which was interpreted by Muhammed and expressed in Arabic by him. Try expressing that view in all but the most progressive Islamic forums today and you’ll get shot down in seconds, but you need to remember that until around 1,000 A.D., there really was no such thing as “orthodox Islam”; rather, there was a ferment of often conflicting ideas, and their success or failure owed as much to politics as to anything else. If Saladin hadn’t overthrown the Fatimids of Egypt, the Ismaili view might now be the dominant one.

This debate about the nature of the Qu’ran fed into debates on how to interpret its teachings in areas where it doesn’t have a specific, unambiguous message. Up until the time just mentioned, the majority view was that the Qur’an was the only absolute authority and that humans should use logical inference and analogy (qiyyas) to apply its teachings in both spiritual and legal matters. Later, though, the debate between the Mu’tazila and the Ahl-i Hadith, or “people of the tradition” (not to be confused with the modern Indian movement of that name) swung in the latter’s favour, with the result that hadith — reported sayings of Muhammed — became a source of authority in their own right. The four schools of Sunni Islam represent different evolutions, with the Hanafi school being the closest to the Mu’tazila and the Hanbali school representing the hardcore of the Ahl-i Hadith. This is relevant even to non-Muslims reading the Qur’an because, as I mentioned earlier, much of what we assume is in the Qur’an actually isn’t there but comes from the hadith collections that appeared a few centuries after the death of Muhammed (who actually banned such compilations).

Lost in Translation?

This problem is compounded by the fact that translations of and commentaries on the Qur’an are often influenced by particular hadith and interpretations thereof. It should be borne in mind that even Arabs do not speak the language of the Qur’an any more than modern Greeks speak the language of Socrates, so even Arabic editions are full of interjections and footnotes. And as mentioned, Western translations, particularly older ones, tend to see Muslim concepts through a Christian lens. A well-intentioned attempt to build bridges between the two religions may result in a misinterpretation of Islam.

All of this has in modern times resulted in a backlash, with modernists trying to strip away the hadith they see as fraudulent or even rejecting them altogether, as in the case of the Quranists, a small but influential group who hold that the Qur’an is actually a lot more straightforward and consistent than people give it credit for. Quranist translations, such as those of Rashad Khalifa, Edip Yüksel and the Monotheist Group, tend towards a fairly simple rendering, and where there is ambiguity due to a word having multiple meanings, they generally opt for a more progressive interpretation. A good example is the notorious verse in Surah an-Nisa which it is widely claimed allows men to beat their wives. Here is Yusuf Ali’s translation (note all the parentheses, which are Ali’s additions):

Men are the protectors and maintainers of women, because Allah has given the one more (strength) than the other, and because they support them from their means. Therefore the righteous women are devoutly obedient, and guard in (the husband's) absence what Allah would have them guard. As to those women on whose part ye fear disloyalty and ill-conduct, admonish them (first), (Next), refuse to share their beds, (And last) beat them (lightly); but if they return to obedience, seek not against them Means (of annoyance): For Allah is Most High, great (above you all).

The word “beat” is indeed a translation of the Arabic verb idribuhunne, from the root daraba. Edip Yüksel lists ten different ways daraba is used in the Qur’an, including “travel”, “set out”, “explain”, “give examples”, and the one which seems to fit here, “leave” or “separate”. Here is a Quranist translation from the Monotheist Group:

The men are to support the women with what God has bestowed upon them over one another and for what they spend of their money. The upright females are dutiful; keeping private the personal matters for what God keeps watch over. As for those females from whom you fear desertion, then you shall advise them, and abandon them in the bedchamber, and separate from them. If they respond to you, then do not seek a way over them; God is Most High, Great.

So what’s a poor non-Muslim (or indeed Muslim) to do? As I said, I am not an academic authority, so I cannot comment on which translations are more accurate; all I can suggest is to compare a number of different ones, especially for those verses that strike you as problematic. (I have adopted this approach for many years with the Dao De Jing, which is so poetic and ambiguous that it makes the Qur’an look like a technical manual.) Fortunately, you do not have to go out and buy lots of copies of the Qur’an; quran.com lets you pick from a wide selection of standard translations, while quranix.org also contains some of the more modern ones.

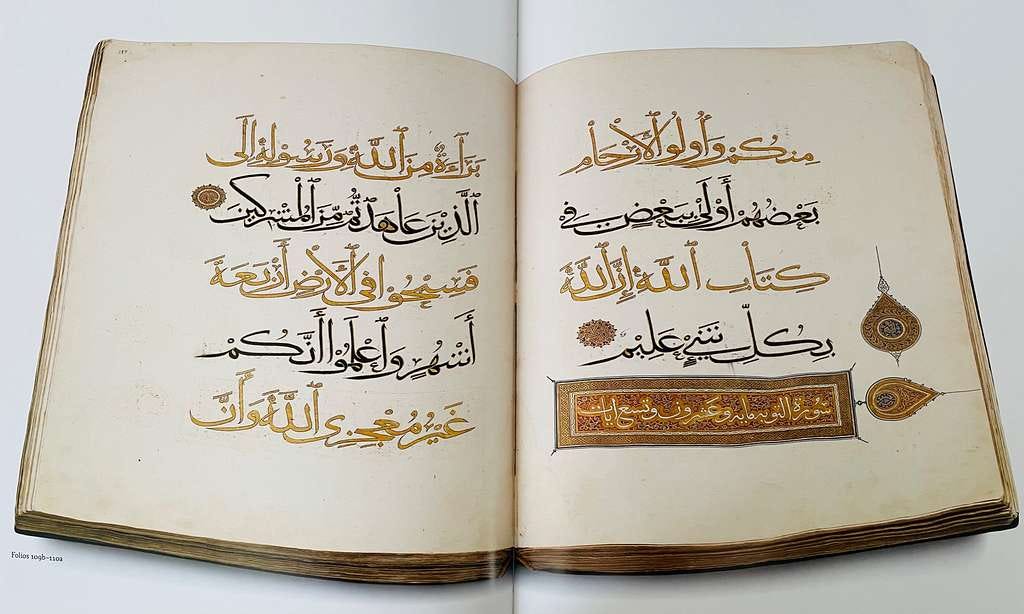

I also suggest trying to read and listen to a couple of surahs in Arabic to get a sense of the aesthetics of the Qur’an. Start with al-Fatiha, which is kind of like the Lord’s Prayer for Muslims or al-Ikhlas.

What About Those Sufis?

Earlier I hinted that Sufis have their own way of reading the Qur’an. This is not to say that Sufism is somehow distinct from Islam, let alone opposed to it; that is a view that arose with Salafists (who were not a significant force until comparatively recently), was perpetuated by some Islamic reformists who wanted to strip Islam of what they saw as superstition, and struck a chord with New Agers who liked Rumi but didn’t want to be bothered by all that religious stuff. While some Sufis have expressed views that most Muslims would regard as heretical and engaged in practices that appear shocking, others are quite conservative in both beliefs and behaviour. What unites them, though, is the view that, contrary to my initial reading, the Qur’an is really, really deep, and requires not only logical analysis to understand but also deep reflection and, ultimately, mystical experience. In fact, it could be seen as a circular process: reading the Qur’an deeply induces mystical revelations which in turn enable a deeper understanding of the Qur’an, and so on. One Sufi teacher, Somoncu Baba, refers to as many as seven layers of meaning in the Qur’an. This reflection or contemplation (tefekkur) is also normally coupled with spiritual practices which vary between different Sufi orders, such as dhikr (mantra-like repetition of the names of God and other key words), music or dance.

Sufi philosophy is far too deep a topic for me to go into here; suffice it to say that most Sufis hold that each verse of the Qur’an has both an exoteric meaning and an esoteric meaning. To give an example, I recently listened to a Turkish Sufi teacher (Rengin Sakaoğlu) discourse on Surah al-Tin (The Fig), which starts “By the fig and the olive.” This line has perplexed scholars, with some claiming it refers to the nutritive properties of these fruits and others speculating that they refer to places where they grow (given that the following two lines refer to places, possibly Mount Sinai and Mecca). On the other hand, this Sufi interpretation (there may be others) invites us to consider the form of the two fruits: the fig has countless seeds, symbolising the infinite names or attributes (asma) of God, while the olive has one, symbolising God’s unity (tawhid). This paradox is a central feature of Sufi philosophy: God is both totally one and infinitely diverse, and we are reflections of this. Similarly, the famous line in Surah al-Ikhlas, lam yalid walam yulad — "He does not beget, nor was He begotten" — can also be interpreted as saying that in our true essence, we are neither born nor do we give birth, because we are simply reflections of God. Similarly, prophets such as Abrham, Moses, Jesus or even Muhammed are seen not just as historical personages but higher states of consciousness (maqam) that exist inside each human being.

As for the verses about women mentioned earlier, Sufis may follow the more “progressive” view of the Quranists but may also deny that the word used in the Qur’an, nisa, refers to women at all but to a state of the heart. I can’t say that I fully understand this, but it reminds me of something my taijiquan teacher Ismet Himmet said about how lines in the Dao De Jing referring to “the people” actually refer to one’s own organs or cells. This relates back to the problem of language; some Sufi teachers maintain that the real Qur’an is not Arabic but in a divine language (Rabca in Turkish, from Arabic Rab, meaning Lord), which is understood by the heart, not the mind.

As I keep saying, I am no authority, but if you like this kind of interpretation, Rumi’s book Fihi Ma Fih (usually translated as Discourses) is full of it. However, if you are not already familiar with Sufism, I suggest starting with something a bit more accessible; like Idries Shah’s collection The Way of the Sufi, or some of the videos on Philip Holm’s excellent Let’s Talk Religion channel, which presents his extensive academic knowledge in a very accessible way.

I hope this has provided some useful information and has encouraged people to read the Qur’an rather than putting them off! Any credit is due to the wonderful authors and teachers that I refer to (or have not referred to); any errors are purely my own.

You're a really amazing writer! I thought this was a fantastic article that you put together.

Of the abrahamic traditions Islam is the one I definitely know the least about. I guess I don't even know if they don't like even being lumped in with the others.

I grew up in such an islamophobic place that about once a week at the library my mom ran: One of the conservative Christian groups would come in and steal the Quran because they deemed it didn't need to be on the shelves. At some point the joke was on the conservative Christians because my mom found at an estate sale 300 of them that the person ended up just giving to my mom. Every time the Quran would be stolen, my mom would just bring another one from the boxes we had in the basement.

At some point at one of the library board meetings they addressed a letter saying that my mom was spending too much money replacing all the quran's that have been stolen... My mom replied by saying that "she didn't know that the book had been stolen because there's always one on the shelf and I think that someone must just keep putting it in the wrong place". (Which was obviously a lie but the board didn't know what was happening)

At some point one of the board members looked at all of the money being spent on new books and was satisfied. At one point, the most conservative church decided to burn banned books and other forms of media Nirvana CDs and D&D books... At one point it was going to be a public event but then they noticed that 90% of the books had actually been taken from the public library with a surprising number of more than 100 quran's... This got reported in the local newspaper and it turned into a private thing out of shame for stealing that many books and destroying them... After the bad press, the church wrote a check for $4,000 as an apology to the library. As the coup de gras of a librarian, my mom purchased a rather expensive swedish translation of the Quran (It was a Scandinavian ethnic town for reference) and it was put into the special collection that was locked.

She also put a pretty hilarious Latin phrase "ferro ignique" (literally fire and iron but has a meaning of scorched earth basically) that she signed by our great uncle who was known as the person that came up with the name for the big festival locally in the late 1800s.

Every time there was a chance to unlock the special Scandinavian collection, she would mention the Quran. One person locally new enough of the story and laughed their ass off. I forget for sure, but I believe two or three professors thought it was an odd inscription. And now that I have been gone for 15 years, this is pretty much the first time I've ever told this story because my mom swore it to secrecy and it's been a long time since I've been in that little town.

I didn't know I was going to tell a story when I first started typing. I really love this article. Thank you so much!